Meniscal tears are a common orthopedic problem that can significantly impact knee function. Various approaches to treatment qualification are found in the literature. In this article, I will shed light on current knowledge about the specific nature of these tears and propose treatment approaches based on current research. A key element of effective therapy is an individualized approach, precise diagnosis, and a rehabilitation program tailored to the specific nature of the injury. A properly planned recovery allows patients to increase their safety in returning to everyday and sporting activities.

History

For many years, the gold standard has been to protect the menisci at all costs and, whenever possible, seek repair options due to their importance and function in "saving the meniscus." This is even more worth publicizing, especially after the major blunder of orthopedic surgery in the 1960s, which involved recommending total meniscectomy even in trivial cases. This view emerged from very low-quality studies with limited follow-up on patient well-being.

A 2021 meta-analysis by Bahns et al. found moderate associations between occupational risk factors and the development of meniscal tears for the following activities: kneeling, squatting, climbing stairs, carrying loads ≥ 25 kg, playing professional soccer, working as a coal miner, and flooring workers. The overall quality of evidence according to GRADE was moderate to low.

Functions of the knee joint meniscus

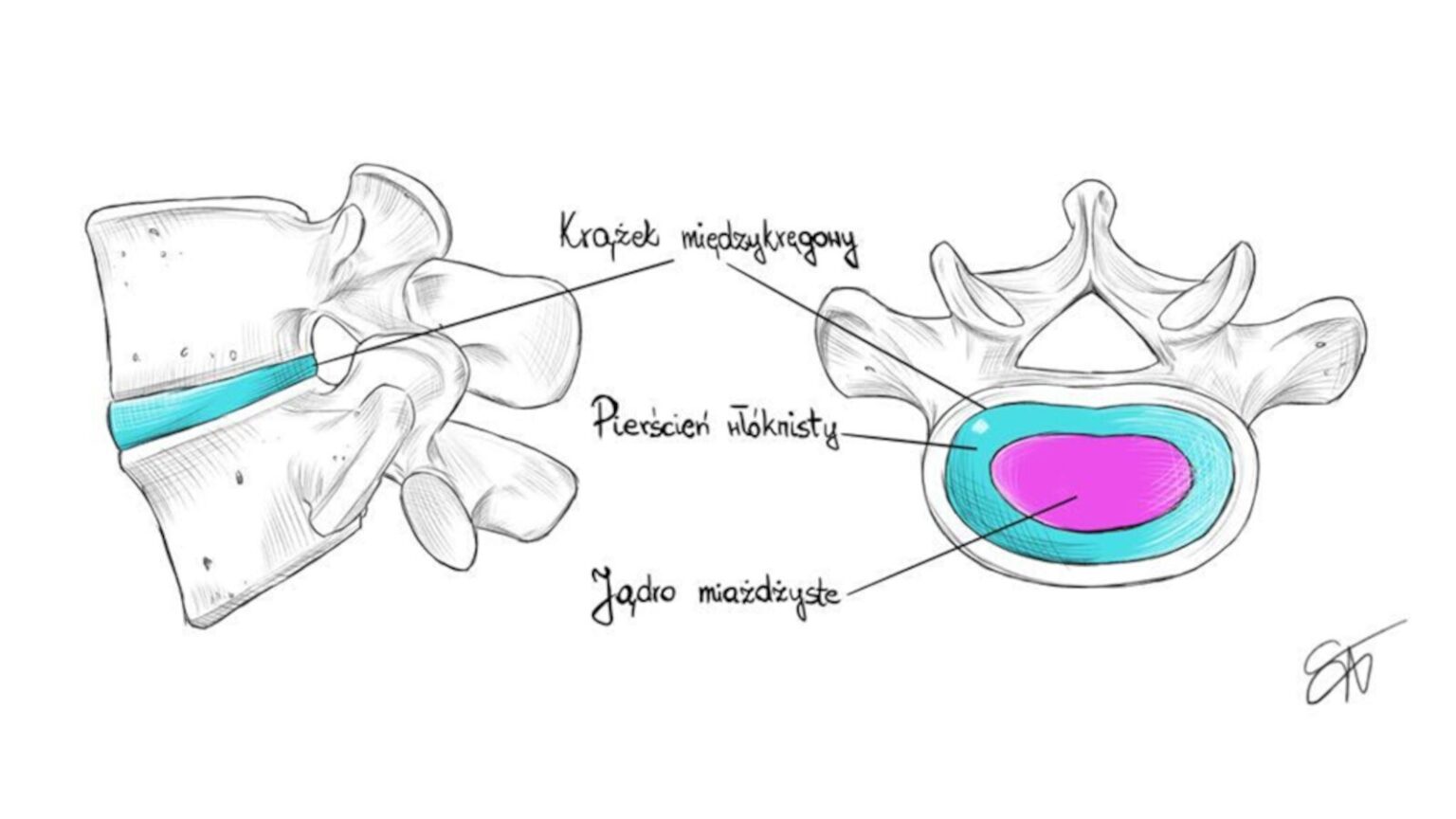

The functions of the knee menisci include: cushioning the knee joint, stabilizing it, participating in joint lubrication, participating in the distribution of nutrients, certain segments of the menisci have sensory/proprioceptive functions, and, above all, playing a significant role in load distribution. The knee joint has two menisci: medial and lateral. The medial is larger, C-shaped, and less mobile due to its connections to the joint capsule and is more susceptible to injury. The lateral meniscus is more mobile and crescent-shaped. Their vascularity decreases with age. This vascularity is divided into three zones, which often determine the predisposition for potential union after injury. The circular "red" zone is the most vascularized, followed by the transition zone, and finally the avascular "white" zone, which is practically impossible to union.

The menisci are pairs of asymmetrical, semicircular fibrocartilaginous structures that are attached to the tibial plateau anteriorly and posteriorly. The meniscotibial ligament provides the connection to the tibia. This structure is composed primarily of bundles of type I collagen and a complex network of fibers with various orientations, providing stability and support.

Most fibers are arranged in a circular pattern, allowing them to resist compression, while radial fibers protect against longitudinal tearing within the circular fibers. This structure develops over the first ten years of life, at which point it reaches similarity to the adult menisci in terms of content and structure. During development, blood and nutrients are supplied from the periphery across the entire width of the meniscus until the ninth month after birth, when the inner third becomes avascular. In subsequent stages of development, this avascular zone enlarges, leaving only the outer 10% to 30% vascularized. The argument for repairing central tears in pediatric meniscuses stems from the belief that, compared to adult meniscuses, they are relatively more vascularized.

Types of meniscus injuries

Meniscal tears are primarily divided into traumatic and degenerative. Traumatic tears that begin suddenly and result in intense pain may also be characterized by locking and limitation of motion, swelling, warmth, and mechanical symptoms such as snapping. They are often associated with other injuries, such as ACL tears (RAMP tears). From a clinical perspective, several criteria should be considered for the diagnosis of meniscal tears: pain at the end ranges of motion in flexion and hyperextension, a positive McMurray test, a positive painful joint space test, and a history of knee locking.

The most common causes of traumatic injuries include rotational sports, which involve components of rotation and lateral joint movement, such as soccer, skiing, and tennis. Injuries can result from mechanical trauma, chronic overuse, or degenerative changes. Their classification, diagnosis, and treatment and rehabilitation approach are crucial to maintaining knee functionality and preventing further damage.

Types of damage:

- Radial

- Horizontal

- Bucket handle (massive vertical with dislocation)

- Longitudinal

- Platelet-type (vertical or longitudinal flap)

- Parrot-beak-type (vertical flap)

- Meniscal root

- RAMP Type

- Degenerative (chronic) injuries

The worst prognosis and failure rate with conservative treatment will be:

- Radial tears: Axial pressure will lead to progressive damage and loss of meniscal function through further tearing.

- Bucket-handle tears: Apparent improvement in range of motion during conservative rehabilitation may actually indicate a worsening of the injury and subsequent difficulties with surgical repair.

- Ramp lesions: lesions of the posterior portion of the medial meniscus, often occurring in patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. They can cause rotational instability of the knee and increased anterior tibial translation. They are often not visible on MRI, so arthroscopic diagnosis plays a key role in their detection.

- Ramp lesions: uszkodzenia tylnej części łąkotki przyśrodkowej, często występujące u pacjentów z zerwaniem więzadła krzyżowego przedniego (ACL). Mogą powodować rotacyjną niestabilność kolana i zwiększoną translację przednią piszczeli. Często nie są widoczne w badaniach MRI, dlatego diagnostyka artroskopowa odgrywa kluczową rolę w ich wykrywaniu.

In recent years, knowledge about RAMP tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus has expanded significantly. Therefore, it is worthwhile to familiarize yourself with this type of injury and its classification. Ramp tears can be vertical, longitudinal, or oblique. Their underestimation results from omissions and inadequate attention during MRI interpretation, as well as the exclusive use of standard anterior ports during arthroscopy.

Studies suggest a RAMP tear incidence of 15-42% in patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. The co-occurrence of these two injuries is likely due to the fact that both structures, the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and the ACL, protect the cruciate bone from excessive anterior translation, and therefore, they can be damaged by a similar mechanism. More data and studies are needed to determine which types of RAMP tears are more stable. Risk factors for RAMP tears include varus deformity, a steep medial meniscal slope, and a medial tibial slope. Chronicity of the ACL tear is another risk factor that may increase the incidence of developing a RAMP tear. Although this type of tear is often missed on MRI, the use of a posteromedial port may be necessary to detect this type of tear.

The menisci, fulfilling complex shock-absorbing and sealing roles, are subject to wear and tear, like any supporting structure in our bodies, as we age. The longer a given injury develops, the less likely it is to experience acute pain and mechanical symptoms. Therefore, the degenerative injuries described are often physiological in nature. Of course, their extent and type will determine their ability to provoke symptoms. Currently, degenerative changes in the meniscus are primarily treated with physiotherapy, NSAIDs, BMI reduction, and viscosupplementation. In the presence of concomitant degenerative changes in the knee joint, arthroscopy is not recommended; however, if these are absent and conservative treatment has failed, arthroscopy may be considered.

Treatment characteristics

In addition to the types of tears, the anatomical classification of meniscal tears is essential knowledge when beginning treatment. The knee menisci consist of two roots (anterior and posterior), two horns (anterior and posterior), and a shaft. This understanding allows for certain nuances in the postoperative treatment approach that will improve patient safety.

The simplest procedure for postoperative treatment is a simple meniscectomy, which carries no specific precautions or contraindications. Standard edema reduction, optimal weight-bearing, and increased range of motion are all performed.

Does the protocol exclude an individual approach?

In the case of meniscus repair (suturing), a greater number of details are necessary to ensure maximum patient safety and an optimal return to their favorite activities. Due to differences in the extent of the injury (suturing size), the type and location of the injury, co-occurring injuries, the patient's fitness level, and the surgeon's recommendations, it is impossible and unwise to blindly follow a single protocol and rehabilitate everyone the same way. We must be vigilant, familiar with the general principles, and listen to our patient. In doubtful situations, due to complexity or insufficient information on the discharge summary, it is advisable to consult with the surgeon.

The result of recommendations resulting from current research is the implementation of a general outline protocol for patients after arthroscopic meniscus repair:

- 4-6 weeks: minimal weight-bearing or complete weight-bearing (elbow crutches).

- 4-6 weeks: 50% body weight, after week 6, full weight-bearing.

- Approximately 1 month: Range of motion limited to 90 degrees.

- First weeks after surgery: Avoid rapid flexion movements, especially under load after treatment of the posterior aspects of the meniscus (posterior root, shaft, posterior horn).

- First weeks after surgery: Avoid rapid extension movements at the end of the range of motion, especially under load after treatment of the anterior aspects of the meniscus (anterior root, anterior horn).

- Up to 8 weeks: No hamstring exercises for medial meniscus repair (e.g., RAMP, root, shaft).

- Range of motion progression based on injury:

- Major injuries: 30-60-90 degrees in 6 weeks.

- Minor injuries: 2-4 weeks – 90 degrees, then 10-20 degrees every following week.

- After 7 weeks: While fully weight-bearing, squat to 70 degrees

- Full flexion without weight-bearing by week 10-12.

- After 3 months: full flexion with weight-bearing.

Summary

Meniscal tears of the knee are a complex orthopedic problem that requires a diverse approach to diagnosis and treatment. Understanding the types of tears and their function is crucial for effective treatment and rehabilitation. Properly tailored therapy and an individualized approach can contribute to improved joint function and a return to physical activity.

Paweł Błachotnik

I graduated from the University of Physical Education in Wrocław. Since 2011, I have been pursuing a career in physiotherapy, which has become not only my profession but also my passion. I have many interests related to physical activity and motor development, as I deeply believe that movement holds the magic of healing and is one of the keys to health. In physiotherapy, I have a particular fondness for orthopedics and traumatology, which is why I have extensive experience with sports in physiotherapy. At FRSc, I conduct my own training. Physiotherapy

in orthopedic injuries Read more...

Check out the course

References

- Chambers HG, Chambers RC. The Natural History of Meniscus Tears. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(6 Suppl 1):S53-S55. PMID: 31169650.

- Bahns C, Bolm-Audorff U, Seidler A, et al. Occupational risk factors for meniscal lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22:1042.

- Fox AJ, Wanivenhaus F, Burge AJ, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. The human meniscus: a review of anatomy, function, injury, and advances in treatment. Clin Anat. 2015;28(2):269-287. PMID: 25125315.

- Bae BS, Yoo S, Lee SH. Ramp lesion in anterior cruciate ligament injury: a review of the anatomy, biomechanics, epidemiology, and diagnosis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2023;35:23.

- Calanna F, Duthon V, Menetrey J. Rehabilitation and return to sports after isolated meniscal repairs: a new evidence-based protocol. J Exp Orthop. 2022;9(1):80. PMID: 35976500; PMCID: PMC9385921.

- Kopf S, Beaufils P, Hirschmann MT, et al. Management of traumatic meniscus tears: the 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(4):1177-1194. PMID: 32052121; PMCID: PMC7148286.

- Mameri ES, Dasari SP, Fortier LM, et al. Review of Meniscus Anatomy and Biomechanics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022;15(5):323-335. PMID: 35947336; PMCID: PMC9463428.

- Rucinski K, Stannard JP, Crecelius C, et al. Accelerated versus Standard Rehabilitation after Meniscus Allograft Transplantation in the Knee. J Knee Surg. 2024;37(10):710-717. PMID: 38388175.